The resighting of Atlante, the scarred sperm whale

Whales impacted by traffic in the Mediterranean

The sperm whale sighted on July 20th was unmistakable. Both biologists and citizen science participants aboard the research vessel “Pelagos,” engaged in the Cetacean Sanctuary Research (CSR) expeditions in the Ligurian Sea, were impressed. The whale’s tail had a strikingly jagged edge, almost like a comb. This individual, named “Atlante,” is missing about a third of its tail.

The flukes are a cetacean’s propulsion organ; in sperm whales, it typically surfaces before a dive, allowing researchers to distinguish individuals. Atlante’s flukes immediately bring to mind a propeller as the cause of the deep scars. Collisions between cetaceans and boats can kill the animals or leave them with severe injuries, which can impair essential functions like feeding, ultimately threatening the population’s survival. Beyond collisions with large ships, ferries or cargos, often cited as responsible for injuring and killing large cetaceans, recreational motorboats in the Mediterranean are also a growing concern.

Sperm whales (Physeter macrocephalus) are regularly living in the Mediterranean and are an iconic species of the Pelagos Sanctuary, the large transnational marine protected area established for whales’ and dolphins’ conservation. In the Mediterranean, there are likely fewer than 2,500 mature individuals, and the declining population is classified as endangered on the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List.

Luckily, Atlante seems relatively healthy. Through the hydrophone, an underwater microphone used for research, Tethys biologists learned more about him: his vocalizations indicated he was feeding, and in acoustic contact with other sperm whales in the area. Atlante was first sighted in October 2021, named by researchers from Menkab – Il Respiro del Mare, who estimated his length at about 8 meters at the time. He has been regularly seen since, both in the Pelagos Sanctuary and in the waters around Ischia.

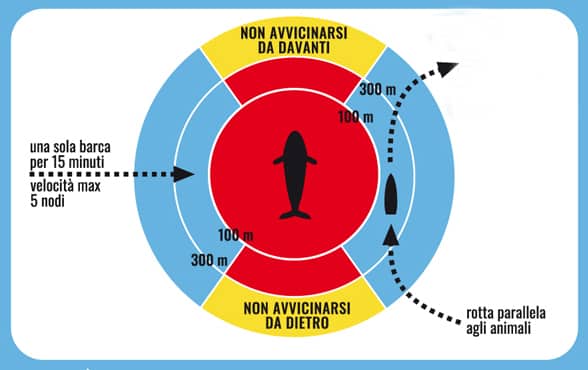

Code of conduct when encountering a cetacean at sea

In summer, the risk of collisions is even higher, with the increase, on one hand, of boats and, on the other, of whales, which come to feed in this season, particularly in the Pelagos Sanctuary. Recreational boats often get too close to the animals at high speed, risking not only disturbing but also seriously injuring them—a behavior often seen in social media videos.

To inform boaters on how to behave when spotting whales or dolphins, Tethys, the Coast Guard, and the italian FAI – Fondo Ambiente Italiano, published a code of conduct a few years ago, distributed in all Italian ports. The goal is to ensure that sighting cetaceans at sea is a wonderful experience without posing a threat to the animals. This guide (in italian) is freely downloadable and aims to protect both the whales and those who enjoy seeing them.

Maddalena Jahoda

Regarding collisions, a positive news: last year, the Marine Environment Protection Committee of the International Maritime Organization (IMO), the United Nations agency responsible for regulating maritime transport, declared a part of the northwestern Mediterranean a Particularly Sensitive Sea Area (PSSA) to protect large cetaceans from collisions

Further on collisions

Tethys is a partner in the Life-Seadetect project which aims to use the most sophisticated technologies to enable ships to detect the presence of large marine mammals.

Atlante is not an isolated case: other animals have suffered accidents due to collisions or other human activities. Among the most known:

- Propeller, a fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus) known since 1998 with a deep scar on its back, immediately suggesting a propeller.

- Codamozza, another fin whale that had completely lost its tail and presumably died in the Gulf of Toulon after nearly a year of agony.

- Mezzacoda, a fin whale with an almost completely amputated tail, spotted by Tethys off Sanremo in 2020. (italian text)

- Siram-Freddy, a sperm whale with a large scar on his back. (Italian text)